“Granny Dinners” Are Trending

Dinner habits are evolving — and younger generations are leading the charge. According to recent data from OpenTable, early dining (4–5 p.m.) bookings rose 13% in 2025, with 53% of Gen Z and 51% of millennials expressing interest in earlier dinner times. By contrast, only 37% of Gen X and Baby Boomers showed the same preference.

Still, 6 p.m. remained the most popular overall dining time, seeing an 8% increase in bookings, while 8 p.m. only grew by 4%. These shifts signal not just a trend in scheduling, but a potential shift in values and priorities around food, health, and lifestyle.

Behind the Trend: Why People Are Eating Earlier

So what’s driving this change? Here are the big factors shaping how (and when) we eat:

1. Health Consciousness

Younger generations tend to place a high value on health and wellness — and that includes meal timing. Eating dinner earlier gives the body more time to digest before bedtime, which may help with sleep quality and blood sugar regulation. Some research suggests that earlier meals can improve overnight glucose control and lipid metabolism compared with later dinners, even when calories are the same.

2. Flexible Work Schedules

The rise of remote and hybrid work means people aren’t bound to traditional 6–8 p.m. rush-hour dinners. Lunches and dinners can shift earlier if workdays start early or if “commute time” simply doesn’t exist.

3. Lifestyle Choices

Gen Z tends to embrace routines that favor early mornings — like workouts, errands, and planning time before the evening — making earlier dinners more attractive and functional.

4. Perceptions of Value and Availability

Earlier dining times often have more seating availability and can be perceived as offering better deals at restaurants compared to the peak dinner rush.

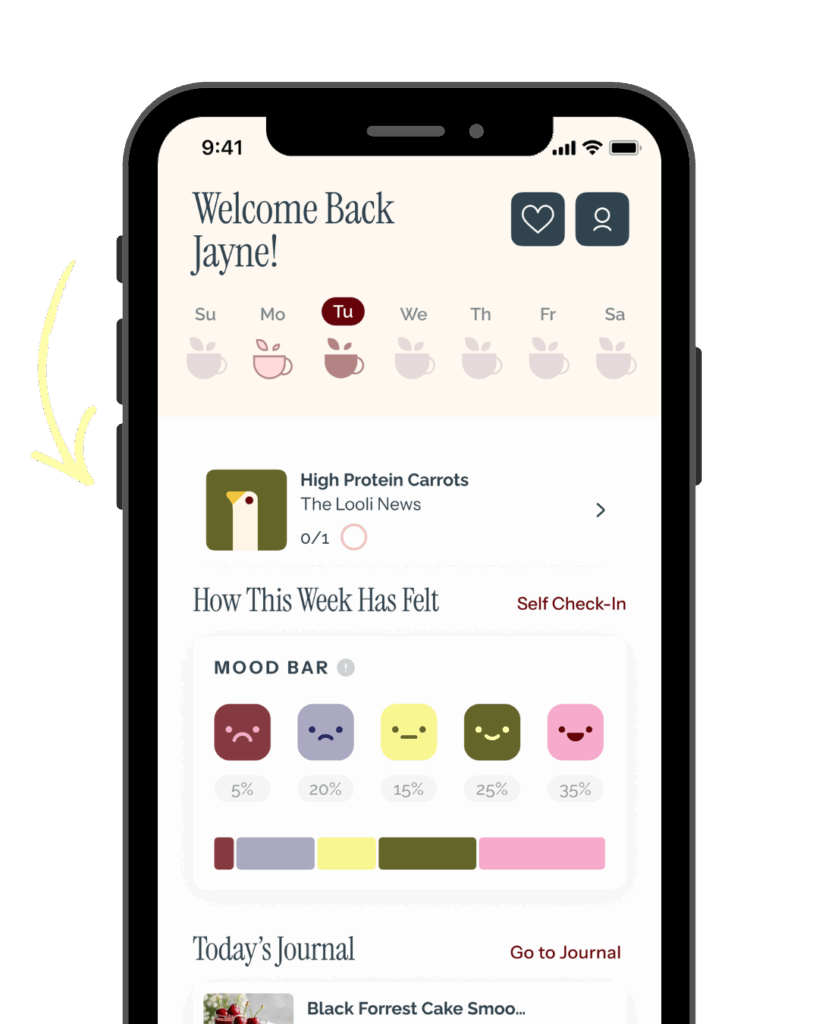

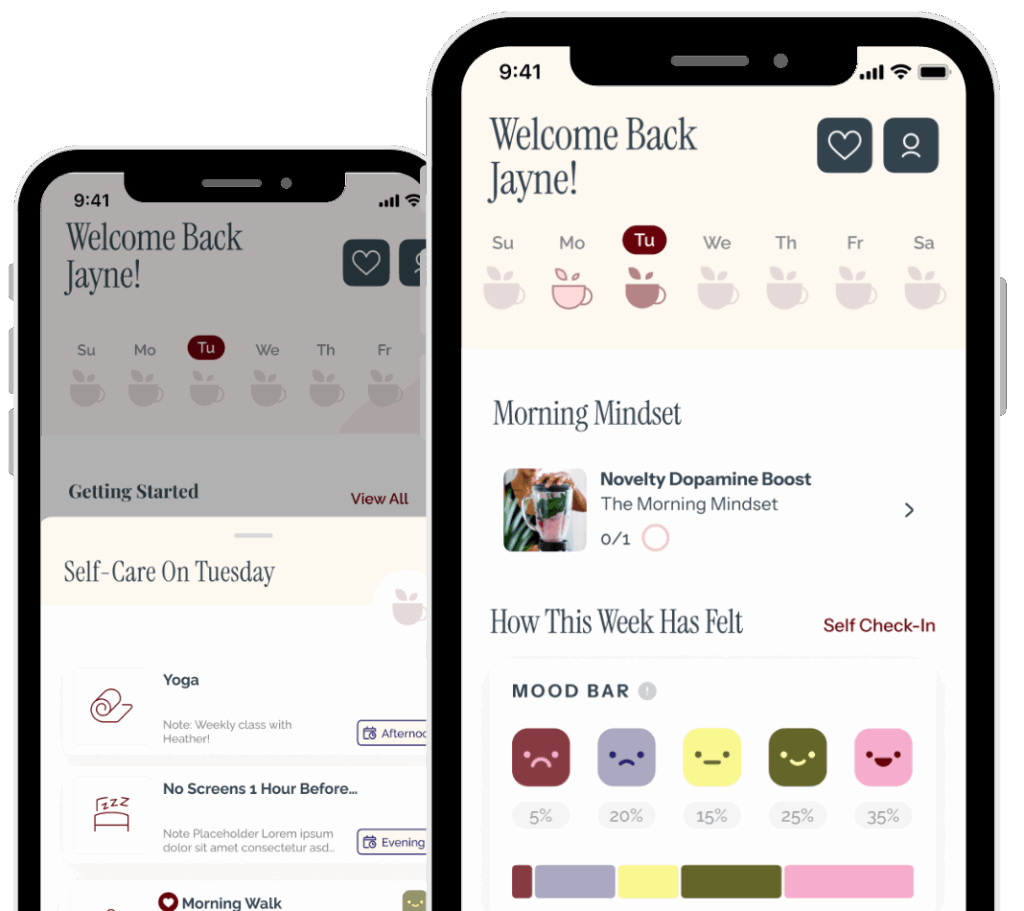

Morning Report Podcast

A short-and-sweet minute morning episode Monday-Friday covering all 3 daily news stories. Exclusively in the Looli App.

What the Science Actually Says About Dinner Timing

Researchers increasingly study when we eat — not just what we eat — and how that interacts with metabolism, hormones, and daily rhythms. But it’s critical to look at what these studies do and don’t tell us about real‑world behaviors.

🧠 Metabolism & Glucose Regulation: Timing Isn’t the Only Factor

Some controlled clinical studies show that the clock time of dinner influences glucose patterns when all other variables (calories, composition) are held constant.

For example, a study found that eating dinner at 6:00 p.m. (vs. 9:00 p.m.) led to lower blood glucose levels throughout the 24 hours and differences in substrate (fat vs. carbohydrate) oxidation the next morning in healthy adults.

However, these controlled settings intentionally strip out life context — such as stress, work schedules, sleep timing, and physical activity — all of which independently affect glucose metabolism. Many people who eat late do so after long workdays, irregular schedules, or stress, and all of those factors can influence blood sugar regardless of meal timing itself.

Other research suggests that energy metabolism and glucose tolerance can vary when meals are delayed, with late eating associated with reduced glucose tolerance under experimental conditions. But again, these lab studies may not fully reflect the adaptations that can occur with habitual late‑eating lifestyles or different sleep‑wake patterns.

⏰ Circadian Biology: Internal Clocks Matter — But People Differ

Meal timing interacts with circadian rhythms — the internal biological clocks that regulate sleep, hormones, and metabolism — but the story is complex.

- One trial examining meal schedule shifts found that delaying meals by several hours altered glucose tolerance and energy use in controlled settings, suggesting that timing interacts with circadian physiology.

- Shift‑work studies show that aligning eating with usual daytime hours (even if sleep is shifted) can help prevent glucose intolerance seen during night work, indicating the importance of circadian alignment when possible.

Importantly, timing effects also appear to have a heritable component: later habitual calorie intake has been linked to lower insulin sensitivity and higher fasting insulin and HOMA‑IR, even after adjusting for diet, sleep duration, and other confounders — but genetics also influenced both meal timing and chronotype (i.e., whether someone is an early bird or night owl).

This underlines a key point: individual biology matters. Some people’s internal clocks may make them more sensitive to meal timing changes than others.

🛌 Digestion & Sleep: Comfort Over Clock Time

Studies in controlled environments show metabolic differences based on when food is eaten, but those findings shouldn’t translate into rigid rules.

Many people who eat later do so because of work, family rhythms, or social schedules. And for them, later meals — especially when spaced comfortably before bedtime — may feel better and cause less stress or hunger than forcing an earlier dinner that doesn’t fit their day.

Research indicates that meal timing and metabolic responses aren’t universally fixed — they interact dynamically with lifestyle, chronotype, and behaviors over time.

Cardiometabolic Patterns: Correlation Isn’t Causation

Observational evidence suggests that eating very late (e.g., within two hours of bedtime or consistently after ~9 p.m.) tends to cluster with other risk factors like sleep disruption, shift work, less consistent eating patterns, and stress — all of which independently relate to poorer metabolic outcomes.

That doesn’t prove late eating causes harm by clock time alone — it means timing is often part of an overall lifestyle context.

What It Doesn’t Say: One Size Does Not Fit All

Here’s the nuanced takeaway from the research:

- Yes, tightly controlled trials under lab conditions show differences in glucose metabolism based on dinner timing, but they don’t capture the full picture of real‑life habits and stressors.

- No, eating dinner late does not automatically mean someone will have worse health outcomes — the context of their day (stress, sleep, food quality, daily routines) matters a great deal.

- Yes, circadian alignment can support digestion and metabolism when combined with consistent sleep and activity patterns, but individual biology and schedules vary widely.

In practice, being mindful of how you feel around meal timing — including digestion comfort, sleep, energy the next day, and stress levels — likely matters more than “eating by X time on the clock.”

The “Don’t Do This” on Dinner Timing

Although science highlights potential benefits of earlier dinners, it’s equally important to avoid rigid “eat by 5 p.m.” rules that can feel restrictive or arbitrary.

❌ What Not to Do

- Don’t force strict cut-offs that don’t fit your schedule or hunger cues.

- Don’t equate earlier eating with better health in isolation — food quality, portion sizes, and overall routine matter just as much.

- Don’t ignore your body: If you’re truly hungry later in the evening, a small snack is okay — especially if it improves your comfort and sleep quality.

Final Takeaway

Dinner habits are shifting — especially among Gen Z — and there’s real science behind why earlier meals may support digestion, blood sugar control, and sleep. But flexibility and mindful eating remain key. Meal timing can be a tool for health, not a rulebook to live by. Listen to your body, align your meals with your lifestyle, and choose what feels best for you.

Download The Looli App

Make your wellness a priority, inside and out!

Start your free 7 day trial and access more tools, resources, content, recipes, workouts and more.